Easter Sunday: 'So, you think you're alive, then?'

Easter Sunday,

2001

As long

as you do not know

How to

die and come to life again,

You are

but a sorry traveller

On this

dark earth. (Goethe)

Those of

you who have travelled on the DART (Dublin Area Rapid Transit) in the last few weeks will no doubt have

seen a poster sponsored by some Christian group or other advertising a number

of screenings of a video with the title ‘The Evidence for the Resurrection’.

The poster appears at Easter time every year, and I have been tempted to

attend, but I’ve always resisted the temptation because I am familiar enough

with the arguments they are likely to bring forward and, since I’ve never found

them convincing when I’ve encountered them in print, I’m hardly likely to be

impressed by them in a slick and simplified video version. How anyone thinks it

possible to provide, in the total absence of any physical evidence, proof of

any event in the past, let alone one as inherently implausible as the resurrection

of a person from physical death, defeats me, but it is a constant preoccupation

of a certain type of Christian outlook, which seems incapable of finding any

meaning in these stories unless they can be understood as having a literal,

factual, historical basis.

It is, of course, the very implausibility of the story

that the argument will exploit: it must have occurred, they will say, because

without it the history of Christianity is unintelligible. Why would the early

Christians have taken as the central tenet of their religion an event so

unlikely, so unprecedented, if it did not happen? And even more pertinently:

why would Christians have been prepared to suffer persecution and martyrdom

over something which was explicable as either pious fiction or deceptive

fabrication?

|

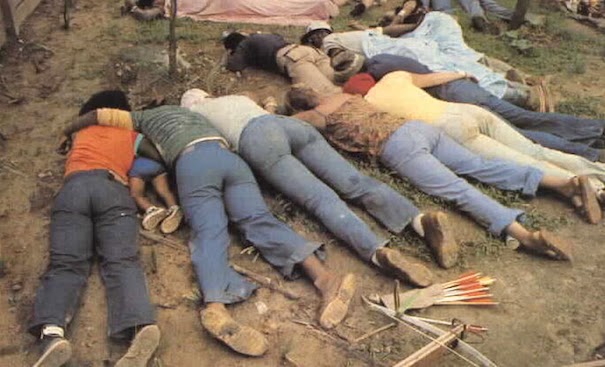

| Victims of the Jonestown Massacre in 1978 |

Such has been the argument of those who uphold the

literal truth of the resurrection stories from time immemorial, and while it

might have carried some weight in the past, we have every reason to be

suspicious of it today. Contemporary events have shown us, again and again,

that religious movements do not begin and do not grow because individual

devotees assess historical and theological evidence dispassionately. Only a few

years ago, apparently intelligent people, members of the so-called Solar

Temple, committed suicide, confident that a space-ship was waiting for them

behind the Hale-Bopp comet; Waco and Jonestown are further examples of the

non-rational nature of religious commitment, and if such things can happen

under our noses there is no reason to suppose that they couldn’t happen in less

rationally orientated times than our own. Faith precedes understanding,

commitment comes before intellectual conviction. As the ancients used to say, fides

quaerens intellectum, faith goes looking for a rational basis for itself

some time after its irrational tenets have been assimilated and accepted at a

deeper level than the purely intellectual.

One aspect of the crucifixion and resurrection

narratives that any apologist for their historical basis has to address is the

significant number of irreconcilable contradictions that the four accounts

contain. For example, Matthew, Mark, and Luke tell us that the crucifixion of

Jesus took place on the day of the Passover; John says that it was the day of

preparation for the Passover, that is the day before. Both are extremely

unlikely, since it is almost unthinkable that the normally prudent Romans would

execute a Jewish criminal, particularly one who was associated with Messianic

expectations, at a time when Jerusalem would be bursting with pilgrims from

around the known world and anything might provoke a riot. But, in any case, by

the simple laws of logic, both cannot be right.

And was Jesus crucified at nine in the morning as Mark

reports, or at midday as John tells us? While researching this address I used

Fr. Ronald Knox’s translation of the Gospels which addresses this discrepancy

in a footnote. It is to be explained, he says, by considering that to people

with less concern for precision than us, the third hour (i.e. three hours after

dawn at 6 o’clock) refers to the whole period between 9 o’clock and midday, so,

if Jesus was crucified at ll.30 it would still be ‘the third hour’. Ronald Knox

was an incredibly talented man, but this little piece of mental gymnastics is

really a forlorn attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable, an example of faith

desperately striving to find a credible intellectual foundation for itself.

|

| Vladimir and Estragon |

Luke’s Gospel tells us that one of the two thieves who

were executed with Jesus repented, an act that is flatly contradicted by

Matthew who says that both thieves taunted him to the end. ‘One of the four

says that one of the two was saved,’ says Vladimir in Waiting for Godot. ‘……….All

four were there, but only one speaks of a thief being saved. Why believe him

rather than the others?’

‘Who believes him?’ asks Estragon.

‘Everybody. It’s the only version they know.’

To which Estragon replies: ‘People are bloody ignorant

apes.’

.jpg) |

| The Angels at the Tomb (Rubens) Two angels or just one? Or was it a man who greeted them? |

Then there’s the story of the resurrection itself. Did

a man in a white robe greet the early visitors to the tomb (as Mark tells us),

or was it an angel (Matthew) or two angels (Luke)? And how come Mark, Luke, and

John missed the earthquake and the opening of the graves which resulted in

numerous people, previously dead, walking about the streets of Jerusalem where,

according to Matthew at least, they were seen by many? This is hardly a detail

that one could overlook.

These are just a few of the numerous historical

implausibilities and logical contradictions with which the four Gospels abound,

and a whole industry of scholarship has grown up around the attempt to explain

or to explain away the inconsistencies and to produce a smooth, uniform account

acceptable to even the most rigorous intellectual scrutiny. Needless to say, it

has invariably failed and the historical credibility of these stories is only

maintained, rather dishonestly, I feel, by the vested interests of scholars who

are drawn, in the main, from the ranks of the clergy, and by the credulity and

continuing ignorance of everyone else who, while professing a belief in the

divine inspiration of the Bible, rarely read it with critical intelligence even

if they bother to read it at all.

Of course, we Unitarians are different. We dispatched

these stories to the trash can a long time ago. They offend our reason and our

perfectly sensible demand that some kind of real evidence should support any

statement before it commands our assent as history. Consequently, in Unitarian

churches up and down Britain and America, the theme today will not be the

resurrection of Jesus, but the springtime resurrection of the earth. Typical of

this approach is Betty Smith’s article in this month’s Unitarian. Betty

writes: ‘Easter is also a celebration of hopeful anticipation and optimism, as

we celebrate the natural renewal of life, and the annual resurrection of

nature.’ (The Unitarian, March 2001)

While we might have some considerable sympathy with

this point of view—at least it has more intellectual integrity than the

self-deluding, historical obsession of much of Christendom—we can only uphold

it, as Betty does, by dismissing the stories of the crucifixion and

resurrection of Jesus as unimportant. ‘I cannot accept that the death of one

man 2,000 years ago can have an effect on my life today,’ she writes. ‘His

death? No. But his life....….that is a different matter.’

There is a third way of approaching these stories,

however, which does not demand that we accept them as historically true or that

we reject them as irrelevant. This third approach (which is really only a

second approach, since the other two are both products of what Rudolf Steiner

calls ‘the dialectical mind’ which, he rightly says, can make nothing of the

Gospels except to reduce them to historical or ethical propositions), is to see

them as stories which transcend the literal and historical categories they have

been placed in by both sides of the polarised debate, and which carry for us a

profound spiritual meaning. What is remarkable about this approach is its

antiquity. The Jews have always held that the scriptures have meaning on at

least four different levels, and the great Jewish writer, Philo of Alexandria,

who was virtually a contemporary of Jesus, wrote an allegorical interpretation

of the Exodus story which is still convincing two millennia on. Another

Alexandrian—Alexandria was a centre of mystical thinking for centuries—Origen,

writing in the third Christian century, has this to say about the problematic

passages in the Bible as a whole and in the Gospels in particular.

(Sometimes) impossibilities are recorded for the sake

of the more skilful and inquisitive, in order

`that they may give themselves to the toil of investigating what is

written, and thus attain to a becoming conviction of the manner in which a

meaning worthy of God must be sought out in such subjects…….He (the Holy

Spirit) did the same thing both with the evangelists and the apostles, - as

even these do not contain throughout a pure history of events, which are

interwoven indeed according to the letter, but which did not actually occur. (Emphasis added. The Works of Origen, Ante-Nicene Library, Volume 1,

page 315)

.jpg) |

| How can light be created before the sun? |

What, then, if we take Origen’s advice and

look behind their historical inexactitudes, contradictions, and

implausibilities, can the crucifixion and resurrection stories teach us? Far

more than I can hope to cover in what remains of this sermon, and, in a sense,

far more than I could ever hope to cover because the only really valuable

discoveries that can be made about such stories are those that the individual

makes for herself. I will just say, however, that, in my opinion, these stories

are not just an unfortunate narrative accompaniment to the sublime ethical

teaching of Jesus (as they are often viewed in liberal theological circles). They

are an integral part of the whole gospel message. The Christian Gospel is not

primarily concerned with history or with ethics; it is concerned with new life,

rebirth, authentic living, which is not to be attained by simply believing the

facts or by keeping the rules. One has to be born again, the new out of the

old, to a radically different kind of life which does not just require the

reform of the old carnal self, but its destruction. The Christian myth tells

us—as all the great religious myths tell us in one way or another—that we are

asleep and that we cannot begin to live effectively and completely until we

wake up. According to the Roman writer, Seneca, a decrepit and dishevelled

member of Caesar’s guard came to the Emperor and asked for permission to kill

himself. Caesar looked at him and said with a smile: ‘So, you think you’re

alive then?’

And this is the question that the Gospels in their

entirety put to us: ‘So you think you’re alive then?’ And then they tell us to

think again. You will never be truly alive, they say, until you reject the life

of comfort and distraction that you so slavishly and so unthinkingly pursue at

the behest of your money-driven, mad society; you will never be truly alive

until you stop associating ease of life with success in life, and until you

stop valuing respectability above authenticity; you will never be truly alive

until you become teachable again like a little child; you will never be truly

alive until you embrace the Way of the Cross, the painful destruction of the

ego and its appetites, and emerge anew, alive, awake, free, transformed, the

old self crucified and the Christ spirit born within you.

This, to me, is the message of the Gospel narrative,

and the crucifixion and resurrection accounts are not just irrelevant addenda,

they are the culmination of a consistent pattern of imagery which describes for

the imagination not just a process that may or may not have occurred in the

life of one man, but one which must occur in the life of each one of us, if we

are to attain that newness of life which is the only hope for our individual

and social salvation.

True religion, far from being the opium of the people,

lulling us back into sleep, should be the adrenalin urging us into life. And

far from asking us, passively, to believe in the historical validity of the

resurrection it should be urging us, actively, to live its existential reality.

A far harder task, indeed, but, we are assured, the most worthwhile task we can

ever undertake.

Comments

Post a Comment