The Baptist and the Christ: Cancer vs Capricorn

The Baptist and the Christ:

Cancer vs Capricorn

(This sermon was given in Dublin on 19th June 2005)

Next

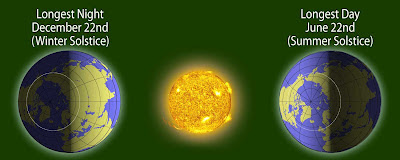

Tuesday, 21st June, is Midsummer Day, the longest day of the year. Barely

will the sun set before it is rising again. In former times, when people were

more attuned to the rhythms of the earth and sky than we are, it was celebrated

with bonfires and feasting, and no doubt the neo-pagans among us will be out in

the woods and on the hillsides, at Stonehenge and Newgrange, on Tuesday,

keeping alive our ancestral customs, acknowledging our dependence upon the sun

for life and livelihood. It’s always been a rather special day for me, because

it was my dad’s birthday – he would have been 98 on Tuesday – and it is also

the anniversary of my ordination to the ministry.

Astronomically it is the day of the summer solstice,

when the sun reaches its point of maximum elevation in the northern hemisphere.

From that point on it will begin its slow decline, the days growing

progressively shorter, until it reaches its lowest point on December 21st,

the winter solstice, when it barely rises before it sets, and motorists are

troubled, even at midday, by the low-lying sun shining directly into the

windscreen.

|

| Mary with John the Baptist and Jesus (Raphael) |

From the very beginning of Christianity, the time of

the summer solstice has been associated with John the Baptist, and his feast

day will be celebrated in Catholic churches next Friday, June 24th. The

ostensible reason for this is that, in the Gospel of Luke, we learn that John’s

mother, Elizabeth, was already six months pregnant with John when Mary became

pregnant with Jesus, so if Jesus was born on 25th December, John

should have been born six months earlier, on 24th/25th

June.

This six month gap in their ages could be a pure

historical accident, of course, but I am inclined to think that their births

have been spaced six months apart in order to identify them with the two

solstices. One clue for this comes in something John says in the Gospel of

John: ‘He must increase, but I must decrease’, which is a perfect description

of the sun’s behaviour between the two solstices: at the summer solstice, when

John the Baptist is born, the sun begins its southerly journey – it

‘decreases’; at the winter solstice, when Jesus is born, it begins its

northerly ascent – it ‘increases’.

And there is a further clue which does not come

directly from the Gospels. In the ancient mystical schools, out of which

Christianity sprang, there was the belief that souls incarnated on earth

through two celestial gates: one gate was the zodiacal constellation of Cancer,

through which human souls came to birth; the other was the constellation

Capricorn, through which the souls of the gods were born. Such thinking is

reflected in Homer’s Odyssey, when Odysseus faces two doorways in a cave in

Ithaca: one, facing north, is Cancer, the door through which human beings may

go; the other, facing south, is Capricorn, and is reserved for the gods. ‘No

mortal feet may pass there,’ says the text. The sun enters Cancer at the time

of the summer solstice, and Capricorn at the winter solstice. John is born

through the gate of Cancer, so his birth is a mortal birth, which helps to

explain what Jesus meant when he said, ‘Of all those born of woman, there is

none greater than John the Baptist; but even the least in the Kingdom of God is

greater than he.’ John represents the finest qualities of a human being, but

Jesus calls us to something higher.

(You no doubt find this astrological stuff strange, but

I stress now as I always stress when I mention these things, that the Gospels

were not written last week by graduates in media studies and journalism from

UCD. They belong to a culture very different from our own, one in which the

starry sky played a very significant part. We forget this at our peril.)

The Gospels contrast the teachings of the two. As we

saw in our reading today, John’s teaching is purely conventional and pragmatic.

He tells those who have two coats to give one away, and those who have plenty

of food to share with those who have none. He himself lives frugally, dressed

only in animal skins, and he eats locusts and wild honey – not a terribly

appealing diet, but one that is hardly likely to upset the ecological balance. His

advice to the tax collectors is, ‘Don’t collect more than you are entitled to

collect,’ and he tells the soldiers to stop extorting money and to be content

with their pay. What John the Baptist is really saying is ‘behave yourself’,

‘do your duty,’ ‘remember that you share the earth with other people and you

must respect their rights as well as your own’. If John were alive today he

would probably be a member of the Green Party, demonstrating at the G.8 Summit

in a duffel coat and sandals, calling for a cancellation of the Third World

debt, while eating vegetarian cheese and wholemeal bread. John would also make

a good, earnest, worthy, Unitarian, convinced that the sum of human happiness

would be immeasurably increased if only we would start to act with a bit more

consideration and civic responsibility. We Unitarians don’t have patron saints,

but if we did John the Baptist would probably head the list.

Contrast this kind of conventional teaching with that

of Jesus. Jesus doesn’t tell us to share what we have, but to give it all away;

he doesn’t tell us to consider the rights of our neighbours, but to love them

as we love ourselves; he doesn’t tell us to fight fairly, he tells us not to

fight at all, even if we have to pay for our submissiveness with our lives. Jesus

doesn’t tell us to keep the rules; he says there are no rules for those who

genuinely love. He doesn’t, like some reformist politician, encourage us to

build a tidier and more just version of the society in which we are now living;

he holds out the prospect of a way of life so radically different from the one

we have now that it will be as if the stars have fallen from the sky and a new

heaven and a new earth have come into being.

Challenging stuff. No wonder we’ve chosen to ignore

Jesus and follow John the Baptist instead. Indeed, Christianity should really

be called Baptistianity, since we’ve opted to go down the route of political

and economic pragmatism outlined by John. And where has it got us? A quick

trawl through any textbook of world history should remind us that we human

beings have never been able to get the political or economic formulae right,

and a glance at the news on any day of the week should alert us to the fact

that we don’t seem to be any nearer finding a solution to our ills than we were

two thousand years ago. Thousands of children will die today because they don’t

have access to clean water. Thousands more will go blind through eye diseases

which are perfectly and easily preventable. The world is torn apart by war

today as it has been since the beginning of time, and I, like many of you, have

lived most of my life under the threat of nuclear annihilation, a threat which

has still not receded completely. Instead of the gradual amelioration of

conditions envisaged by our optimistic ancestors, the last century witnessed

the cruel death is warfare of more people than at any other time in the past. By

the bitterest of ironies, the 20th Christian century was more bloody

than the first. And just last week, a new biography of Mao Tse Tung claims that

this man, hailed by so many in China and throughout the world as a political

saviour, was responsible for the death of 70 million Chinese people, putting

him above both Hitler and Stalin as the 20th century’s most

notorious political tyrant.

Closer to home, the marching season will soon be

getting under way in the north, and last night UTV showed film of the first

salvos being launched – the stones, the water cannons, the riot shields, the

ambulances. And although we in the developed west may have cleaner bodies,

better diets, and longer lives than our ancestors, the aimless hedonism of our

material prosperity only serves to highlight our cultural and spiritual

bankruptcy. Last week’s Searchlight programme was asking why 300 young people –

mostly men – have committed suicide in the past few years in Northern Ireland. And

our prosperity has not freed us from vindictiveness and spite. (This is a

trivial but telling example.) A little while ago, the highly respected British

radio broadcaster, John Humphries, said that his ten-year-old son could read

the news better than Huw Edwards or Fiona Bruce (he was really complaining

about the high salaries these T.V. presenters earn). A few days later, Hugh

Edwards – smart, intelligent, urbane, educated, sophisticated – got his own

back in a speech, referring to John Humphries as ‘the dwarf, John Humphries’. I

despair when I read such things. What chance is there of peace and harmony, of

a genuine new world, when even our most accomplished citizens see fit to trade

hurtful insults like this?

The answer is, of course, that there is no chance. We

are going to hell in a handcart, and our best efforts seem to be devoted to

damage limitation. And Bob Geldof – a reincarnation of John the Baptist if ever

there was one – is currently goading us all into action on behalf of Africa’s

dispossessed and starving millions, but even his heroic efforts will have

little more than cosmetic effect, as he himself will freely admit.

Concentrating on that which is purely human within us,

that which is symbolically born at the summer solstice, has failed and is

destined to fail, for the simple reason that, as the children’s story today

illustrated, none of us is, in our human nature, fit to plant the tree which

will yield the golden peaches. But we are forgetting the other side of the

polarity, that which is born at the winter solstice, the divine nature in which

we all, as sons and daughters of God, participate. Mystical Christianity –

along with the mystical strands of all the spiritual systems – teaches that we

are more than physical organisms, more than random assemblages of molecules,

more than super-intelligent apes. It tells us that all of us, without

exception, have, as the Quakers say, ‘that of God within us’, that we are

sharers in the creative process, ‘gods in ruins’ as Emerson put it. The secular

philosophies which dominate the intellectual world in the materialistic west

have done their best to drive such thinking from our consciousness, with catastrophic

results I might add, and even the conventional Christian systems seem to imply

that we can only become adopted sons and daughters of God if we behave

ourselves and if the right magical formulae are chanted over our heads. When

the Calvinist, Ian Paisley, was asked, ‘Surely we are all children of God,

aren’t, we?’ he thundered in reply, ‘No, we are not. We are children of wrath!’

This, along with countless other misguided theological and philosophical

attempts to stress our sinfulness, our wickedness, and our insignificance has

succeeded in rendering us little better than naughty squabbling, children, fighting

for the last biscuit on the plate.

But Jesus, symbolically born as the light is born at

the winter solstice, calls us to recognise our divinity, and tells us that when

we do, when we acknowledge our oneness with God and with each other, when we

crucify the false self of the grasping, fearful ego, and discover our true

identity as sharers in the divine essence, the kingdom of God will appear automatically.

It won’t come with politics. As the Italian journalist

Tiziano Terzani wrote just before his death: ‘I have always had great sympathy

for revolution. I was in favour of the Vietnamese revolution, the Chinese

revolution – all revolutions interest me. And now I realise; all the external

revolutions have changed nothing, have only created more violence, more death,

more tears. So there is only one possible revolution, the spiritual one, that

each person has to learn by himself, but probably all together, can change the

fate of mankind.’

We have put our hopes in the way of John the Baptist,

the political way, and we have no option but to keep following it. But

remember, John is only the precursor, the forerunner. John, like Moses, could

never take people into the Promised Land. That role fell to Joshua, whose name

is just the Hebrew equivalent of the Greek name Jesus. The way of Jesus is the

way of internal, spiritual revolution. It’s time to rediscover it and give it a

try.

Comments

Post a Comment